There is one curious sidebar to the early history of Lakeview-then-Hillcrest Golf Club. It concerns the notion that half of an entire neighborhood of St. Paul could have become golf course grounds.

Preposterous, right?

In the end, probably yes. But maybe, just maybe, not if Charles Gordon had had his way.

The year was 1921, the month December. It was shortly after — barring some all-time Month No. 12 heat wave that I don’t know about — Lakeview Golf & Country Club had concluded its first season of play on a thin, rectangular plot at the northeastern corner of St. Paul, in what is now known as the Hayden Heights neighborhood. (Lakeview would become known as Hillcrest in 1923. Photo at the top of this post shows Hillcrest, now a Minnesota lost golf course, at Larpenteur Avenue in April 2019.)

If a two-paragraph entry in the Dec. 30 Minneapolis Star is to be believed, someone had bigger plans for the neighborhood than a mere 18-holer.

“New Club for St. Paul,” read a sub-headline on a longer story.

“A new golf club is planned for St. Paul which probably will be one of the largest in the northwest,” the entry began. “The club will have over 2,000 members and will be a 36-hole course.

“C.W. Gordon of the Somerset club is one of the principal backers. The club will be for the salaried men and the annual dues will be $25. C. Raynor will be employed as architect. The course will be built on the tracts of land near the Lakeview Club.”

Well, knock me over with a featherie.

Where do I start?

A) I never heard of such a thing.

B) Two thousand members? (Yes, the story read 2,000, not some other number.) That is preposterous on its face, even knowing that in 1921 golf in Minnesota and the Twin Cities was entering a decade of tremendous growth.

C) Thirty-six holes, with 18 in the neighborhood having been dedicated just months before? Seems unlikely, and I’ll get to more of that.

D) Did someone say Raynor?

There is this, in defense of the Star story: C.W. Gordon was a man of considerable means, so the idea that he had grand plans should come as no surprise.

Charles William Gordon was president of Gordon & Ferguson, a St. Paul clothing manufacturer and wholesaler. His family lived at 378 Summit Avenue and was well connected in business and sporting circles, tied to The Minikahda Club, Town & Country Club and then the patrician Somerset Country Club in Mendota Heights, of which Gordon was a principal founder in 1919. Gordon was so well connected, in fact, that he served as a pallbearer at the 1916 funeral of St. Paul railroad and banking magnate James J. Hill.

Gordon helped establish Somerset in part because he believed Town & Country Club had become overly congested, Rick Shefchik wrote in his classic Minnesota golf book “From Fields to Fairways.” Perhaps that same notion led Gordon to believe there was a similar opportunity in St. Paul’s northeast, where Lakeview/Hillcrest was founded in part as a response to perceived overcrowding at nearby Phalen Park Golf Course, established in 1917.

Still, it’s a stretch to think that area could have reasonably accommodated 36 more holes of golf. After all, even as early as 1921, three other clubs — Phalen, Lakeview and Northwood Country Club in North St. Paul — were already operating within five miles of the 36-hole site proposed by Gordon.

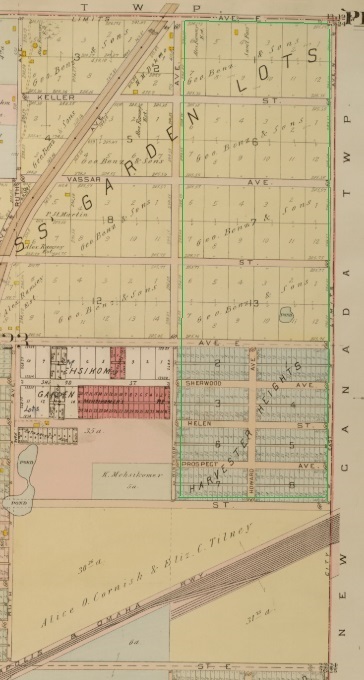

If you ask me, and I know you didn’t but I’m going to tell you anyway, I don’t see how 36 more holes would have fit into this area. (I’m operating under the assumption that the Star story referred to property only in St. Paul and not adjacent Oakdale or then-New Canada townships.) Here’s a 1916 plat map, closest to 1921 I could find:

After all that, here, at least if you are interested in golf history, is the most curious sentence in the Minneapolis Star report: “C. Raynor will be employed as architect.”

C. Raynor? No, frankly, I don’t see that.

The “C” most certainly was a typographical error, and the Raynor reference should have been to “S.,” or “Seth,” or “nationally renowned golf course architect Seth Raynor.” There was in fact a direct connection between Seth Raynor and Charles Gordon. Raynor was the architect hired by Gordon and other Somerset members to design their Mendota Heights Club in 1919, and while in Minnesota during that time period, Raynor also designed Midland Hills in Rose Township (now Roseville), which opened for play in July 1921.

But I know of no connection between Raynor and a proposed golf course in northeastern St. Paul, and none of a handful of informed golf-history sources I talked with knew of one, either.

My bottom line, I guess, is that all of this is a certain amount of ado about nothing. I’m thinking Mr. Charles W. Gordon concocted some sort of brilliant-in-his-head plan in 1921, fed it to a Minneapolis reporter late that year, and that nothing tangible ever became of 36 holes and 2,000 members and Seth Raynor in Hayden Heights.

But it’s interesting to imagine.

Thanks to Minnesota History Center oral historian Ryan Barland for digging up the Minneapolis Star story on Gordon and golf.